Close to three years after it was passed in parliament, a global freedom of information expert has highlighted major deficiencies in the transparency law which must be addressed through amendments if the act is to fulfill the purpose for which such laws are intended – to empower citizens, reduce corruption and mismanagement, and increase accountability.

.Digital.Disclosure. / ALISON LOWE

An assessment of the Bahamas’ Freedom of Information Act 2012 by a global right-to-information expert has found it to be seriously lacking – containing provisions that are “inherently offensive” to the public’s right to know.

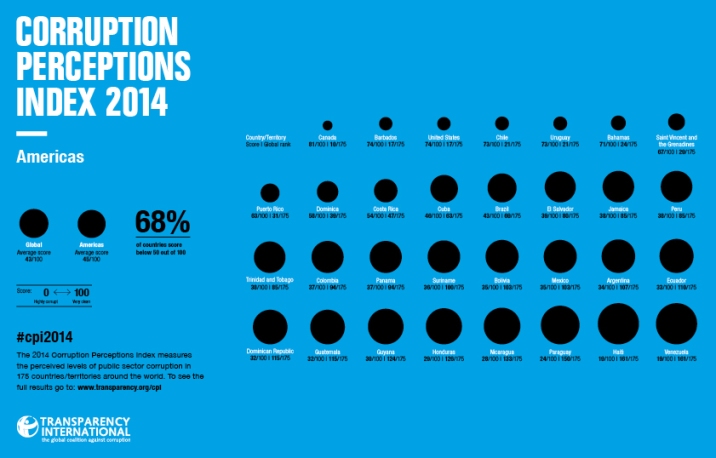

Scoring 59 per cent in a rating of the law against international best practices, global freedom of information (FOI) advocate and human rights lawyer Toby Mendel told .Digital.Disclosure. that the myriad weaknesses of the Act, passed in 2012 but never enforced, represent areas that FOI campaigners in The Bahamas should “fight hard” to amend.

These include a rare right accorded to the government minister responsible for information to provide “absolute” exceptions to information disclosure upon request and a scope of coverage that excludes a wide range of powerful public authorities from accountability under the law from the outset. Among these: non-statutory bodies such as the Bahamas Investment Authority, the Bahamas Environment Science and Technology (BEST) Commission, the National Economic Council, the police, Immigration and the Defence Force.

Mendel, Executive Director and founder of Canada’s Centre for Law and Democracy, a Canadian-based human rights non-governmental organization specialising in freedom of information and expression, has also suggested that government’s proposed delay of considering the passage of the act until Spring of 2016 is “not appropriate” given the well-developed status of the law.

Although “problematic” in a variety of key areas, amendments and preparations to implement the law could be undertaken much more swiftly with the requisite political will.

“That’s just screwing around,” said Mendel of Minister of education, Jerome Fitzgerald’s suggestion that the government would wait until next year to advance the Act, first tabled in 2011 and passed in 2012.

“Given that the law is so developed at this point that’s really unacceptable… It’s not appropriate and they need to move forward and pass this thing,” said the FOIA advocate.

His comments were made in a recent Skype interview with .Digital.Disclosure.

A consultant to governments and entities such as the World Bank and the United Nations on FOI issues, Mendel’s findings essentially suggest that the Bahamian government passed an Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) in 2012 that is at present more of a symbol of a commitment to the principles of transparency and accountability than a workhorse that will get the country there; a paper tiger that makes mention of some of the right terminology but fails to back it up with provisions that assure it.

Although the law performs more strongly in its provisions on procedures – the “how” of information access – it falls down on the “by whom”, the “what” and the “where from” of information disclosure, making this remaining strength fairly meaningless.

There is also an unclear relationship between the law and the Official Secrets Act – a century old law which makes it an offence for officials to disclose information received during the course of their employment. That law entrenched the very opposite of freedom of information and has been acknowledged by successive governments and FOI advocates to have encouraged a culture of secrecy among civil servants; a culture which arguably does as much today to inhibit the public accessing information that is rightfully its own as any legislative initiative.

Mendel came to his conclusions about the Bahamas FOIA after analysing the law using his Centre’s Right to Information Rating system (RTI rating), a respected international benchmarking system used to analyse the quality of the world’s freedom of information laws.

The rating assesses the provisions of the law in the following areas: right of access, scope, requesting procedures and exceptions and refusals, appeals, sanctions and protections, promotional measures. Points are deducted from a maximum score available for each instance in which the law fails to meet international best practices in these areas.

After being measured against these indicators, The Bahamas’ FOIA scores 88 points out of a possible 150, or 59 percent.

This less than stellar score is in fact above average.

However, Mendel said the reality is worse than it appears, for two reasons.

Firstly, the rating itself is based on standards defined some time ago when FOIA regimes were in their early stages. The more recent crop of FOIAs have tended to be more liberal – legislating for greater access to a wider variety of information held by government who pass them.

By comparison to its “peer group” of more recently formulated FOIAs, the Bahamas FOIA would score even more poorly.

Secondly, there is the issue of which portions of the law cause The Bahamas to lose the most points in its rating.

While scoring reasonably well in the area of provisions related to “requesting procedures” and “appeals” under the law, The Bahamas disproportionately drops points in the area of the “scope” of the law (scoring just 10 out of 30 available points) and “exception and refusals” (11 out of 30 available points), due to its serious limitations on who can access information, under what circumstances, and in what form.

Mendel argues that with this level of restriction over what information can be accessed under the law, having a strong appeals system or simple requesting procedures becomes relatively meaningless.

“You can look at the raw score and you can look at where the weaknesses lie. If the weaknesses were better distributed it would be better, but they are fairly concentrated in the scope and exceptions (portions of the law),” Mendel pointed out.

“There are weaknesses throughout but those two areas are particularly weak and those are the two most serious ones because if the law doesn’t cover enough bodies and they have too many exceptions to deny (the right of access) then it’s just not covering the enough stuff. ”

We present in the findings of Mendel and the Centre for Law and Democracy on the Bahamas FOIA, in the hope that the amendments which the government has now indicated are being sought before its implementation will reflect these serious concerns about its efficacy in its present form.

Mendel’s analysis of the FOIA, portion by portion:

SCOPE

The scope of the legislation is the bare bones – the foundation on which everything else is built.

This part of the rating is designed to consider who can access information, what information they can access, and in what form. It looks at whether the executive branch, the legislature, judiciary and state-owned enterprises are covered by the law. Specifically it questions whether the head of state, statutory and non-statutory bodies, police, the armed forces, and other authorities are required to provide information if requested under the law.

In this area, the Centre for Law and Democracy ascribed The Bahamas FOIA just ten out of a total of 30 available points – or a rating of just 33 percent.

It was in this area then, that the law appears to fall most woefully short of acceptable standards.

Among the most glaring omissions in what is covered are the restrictions in who can use the Act to access information. At present only Bahamian citizens and permanent residents can make requests.

“Definitely you should push for legal entities to be able to make requests. The way I understand it, it’s only citizens and residents as individuals who can make FOIA requests in this law. And everywhere (else) allows legal entities to make requests (in their FOIAs),” said Mendel of this shortcoming.

If a legal entity could make a request, this would mean that a non-governmental organisation could do so on its own behalf, or a company, for example. In most developed countries, it is these two types of legal entities that are among the most frequent users of FOIAs, using the information they obtain to push for legislative changes based on evidence of how government policy impacts their industry or issue.

Another major lacuna in the law is that it only applies to statutory bodies. A statutory body is one set up by the government and established in the law as having responsibility to carry out certain functions on its behalf. At first glance, Mendel said the fact the law only applies to statutory bodies may not be a problem if there are no non-statutory bodies of great importance to the conduct of public affairs in The Bahamas.

As it turns out, however, there are.

As pointed out by activist human rights lawyer, FOI advocate and Queen’s Counsel, Fred Smith, there are many “pivotal organisations” in the Bahamian system of government that are non-statutory.

These includes the Bahamas Investment Authority, the National Economic Council and the Bahamas Environment Science and Technology Commission (BEST) – entities which, among other things, make major decisions on what foreign direct investments, hotels and other commercial projects, get developed throughout the Bahamas, setting the path for our economic development and major environmental impacts along the way.

Mendel said: “In some countries practically all of the bodies created by ministries are statutory in nature, but in other countries ministries create non-statutory bodies to do things. That’s a perfectly legitimate way of doing business, but only if those non-statutory bodies – bodies which are controlled by ministries – are covered by the (FOIA) law. Your law does cover statutory bodies, however if in practice there are a lot of non-statutory bodies, which is the case in most countries, then that’s a big hole in the law too.”

Yet another major problem identified by Mendel is the exclusion of the police and the Royal Bahamas Defence Force as bodies which are covered by the law. The Department of Immigration is also excluded.

“Excluding the armed forces and the police is ridiculous. They describe them in the law as ‘security and intelligence services’ (but) the police force is not a security or intelligence force, it’s a police force. There’s a difference between excluding intelligence forces, which is not legitimate anyway, and excluding the police or defence force. No one excludes the police or the armed forces,” said Mendel.

Certainly in the case of The Bahamas, advocates would argue that information held by the police and RBDF would be some of the most sought after, by both the media and the public. For example, records of complaints against police and how, if at all, they were resolved, or records relating to immigration enforcement and conditions at the Carmichael Road Detention Center.

Beyond this question of what bodies are covered by the law, the section on “scope” also considers what types of information they must hand over under it. Further inhibiting the impact of the law on the accessibility of information, the Act restricts what can be accessed to “public records”, including only records that are “held” by a public body “in connection with its functions”.

Specifically, it refers to any record that falls into the definition of a record “in writing; a map, plan, graph or drawing; a photograph; a disc, tape, sound track or other device in which sounds or other data are embodied, whether electronically or otherwise, any film, negative, tape or other device”.

What it does not allow for is the accessing of “information” known to the agency generally, as many laws do, rather than simply records held, or information which might not be considered to be held “in connection with the functions” of the agency.

Three out of a possible four points are lost in this section due to the fact the legislation does not provide a right of access to information held by the judicial branch of government, including both administrative and other information. In the Bahamas’ case, only “administrative” judicial information is covered.

Further restrictions appear as to which State-owned enterprises would be required to hand over information under the law. In this case, only those which are 50 percent or more owned by the government would be covered by the law, and even in these cases the Minister can take them off the list of accountable entities.

EXCEPTIONS AND REFUSALS

This portion of the rating is designed to look at the extent to which and under what conditions the disclosure of information can be refused or excepted in certain cases and if the provisions for exceptions to the right of access are consistent with international standards

In this area, the Centre for Law and Democracy ascribed The Bahamas FOIA just 11 out of a total of 30 available points – or 37 per cent.

Among the ways in which the Bahamas FOIA allows for exceptions to disclosure in the Bahamas include if a request may “unreasonably divert resources”, if it is considered to be against the public interest at that point in time, if the material would be “defamatory” to any individual, if it would “prejudice the effective conduct of public affairs”, if it would be deemed to have a “substantial adverse effect” on the government’s ability to “manage the economy”

On the issue of the law’s exception to the disclosure of “defamatory” information, Mendel suggested this is among the more egregious of the law’s provisions. He pointed out that defamation, by definition, relates to false claims made about an individual that could damage their reputation.

“If the government holds a defamatory statement about me then I’m damned if they’re going to keep that to themselves. I want to get it out so I can denounce it – and say I am not a liar or a cheat. It’s completely unjustifiable,” he said.

Meanwhile, although the FOIA does include an important “best practice” provision known as a “public interest override” clause, which allows for even exempted information to be disclosed if any harm associated with doing so is deemed to be outweighed by the overall public interest in doing so, the RTI Rating lops points off The Bahamas FOIA’s score for including a provision limiting the potential application of the public interest test. Among the areas where the public interest test will not apply to exempted information held are if the information relates to: national security, Cabinet confidences and law enforcement.

Overall, there are seven areas where exceptions to disclosure provided for in the law are not legitimate, Mendel finds.

“Better practice is to say that even though information is exempt, if the overall public interest is served by disclosure of the information, for example because it discloses evidence of corruption or human rights abuses or something like that, then we’ll still make it public.

“That’s a very important override because it makes sure that information gets made public when it should basically.”

“(National security, Cabinet confidences and law enforcement) are very important exceptions (to the application of the public interest override test in The Bahamas FOIA). National security can get abused like crazy and it’s exactly the kind of area where the public interest override can help to lever out corruption, human rights abuses, or whatever it might be. So I think that’s another pretty important (area to focus calls for amendments),” said Mendel.

Going yet further in its detailing of provisions which take away rights to information that it initially appears to allow for, the law provides for the Minister responsible to issue “ministerial certificates” that exempt certain information that would otherwise be available under the Act from disclosure.

Mendel simply described these certificates that the Minister can issue based on requests made to him by those seeking to avoid disclosing information which they would otherwise be required to under the law as “nuts”.

“Your ministerial certificates are incredibly broad,” he explained.

Most importantly, once granted by a Minister, his decision in this respect is “absolute”.

“It can’t be questioned by the information commissioner or by the courts. So basically if the minister says it is exempt it is exempt.” said Mendel.

This type of certificate is “inherently offensive”, very rare in FOIA laws around the world, and likely to be particularly problematic in a small society like The Bahamas, suggested the FOI expert and advocate.

“In a bigger country, you can’t just shunt everything up to the minister but in a small place like The Bahamas I guess everyone is reasonably close and…and it’s easy to say ‘We need to exempt this information’, so I think that’s a really serious thing.

“Ministers can’t take away rights; it’s a right, it’s a human right, and you just can’t take those things away.”

Finally, the RTI-rating analysis of the FOIA flags up the law’s relationship to other laws that already exist as a cause for concern.

One of the “best practice” provisions which are sought in the FOIA by FOI advocates are that the law would “trump restrictions on information disclosure (secrecy provisions) in other legislation to the extent of any conflict”.

However, in The Bahamas’ law it is “very unclear” whether the rights to information it initially purports to generate prevail generally over the right to restrict access to information that arises from laws such as the Official Secrets Act, which has been the bedrock of government secrecy in The Bahamas since 1911.

“The relationship with other laws is a very unclear matter and a very important one. It may be that no one has thought it through. If there’s a conflict between the Official Secrets Act and the FOIA in terms of an exception, which one is supposed to prevail?” questioned Mendel.

REQUESTING PROCEDURES

This part of the rating is designed to look at the “how” of making FOIA requests – how does the law specify we go about it, how difficult or simple it is, whether there are “clear and reasonable timelines” spelled out within the law within which officials must respond to requests, and how much it may cost to file a request.

In this area, the Centre for Law and Democracy ascribed The Bahamas FOIA a better 21 out of a total of 30 available points – 70 percent.

RIGHT OF ACCESS

The right of access indicator looks at whether the legal framework recognises a “fundamental right to access information”, creates “a specific presumption in favour of access to all information held by public authorities, subject only to limited exceptions”, and “contains a specific statement of principles calling for a broad interpretation of the RTI law”, or emphasises “the benefits of the right to information”.

In this area, the Centre for Law and Democracy ascribed The Bahamas FOIA three out of a total of six available points – or a rating of 50 percent.

The rating marks down the Bahamas law for failing to recognise that a fundamental right to access information exists and for not having a specific statement calling for a broad interpretation of the law.

APPEALS

This part of the rating is designed to consider whether and in what form appeal mechanisms exist in the law, which would allow those requesting information to easily challenge decisions made and expect an independent and fair response.

In this area, the Centre for Law and Democracy ascribed The Bahamas FOIA 26 points out of a total of 30 available points – or a high rating of 87 percent.

Mendel described this as an area of strength in the law, but again, one which becomes less important if – as is the case in the Bahamas FOIA – the law does not provide wide ranging access to information to begin with.

“Having a good oversight system, which you have, is very, very important to the success of this system and especially to levering things up as you go along,” he said.

SANCTIONS AND PROTECTIONS

Among the best practices expected in an FOI are sanctions against those who seek to undermine the right of access to information provided for in the law, for example through the unauthorised destruction of information that might otherwise be disclosed. Protection of officials who act in good faith is also key to the law’s effectiveness.

In this area, the Centre for Law and Democracy ascribed The Bahamas FOIA 50 percent – four out of a total of eight available points.

While the law has provisions which can be used to impose a $10,000 fine or prison term of not more than six months – or both – on someone who tries to block access to information, this was reduced from the $100,000 that existed under the first form of the Act.

Meanwhile, the law does not allow for any sanctions against a public authority which “systematically fail to disclose information or underperform(s)” its duties in this respect, the rating finds.

For the first time in Bahamian law, the Act provides good protection for whistle blowers, shielding from legal, administrative or employment-related sanctions if they disclose evidence of wrongdoing.

It also protects the staff of the information commission when they act in accordance with the law – all important to encouraging civil servants to do away with the culture of secrecy that has pervaded Bahamian society and officialdom for decades.

Ironically, however, it does not provide good protection for every official who may act “in good faith” under the law, whether they were later deemed to have “correctly interpreted it” or not. This is a problem, in Mendel’s view.

“So in other words, if an official gets a request for information and they say, ‘OK, I think this material is not covered by the exemptions’ and they give it out, but later on a court decides that it is covered by the exceptions, so they made a mistake, are they going to be liable under the Official Secrets Act and go to prison for 15 years? If they are, they’re not ever going to give out information because they’ll always worry about the Official Secrets Act. So they’ll always be looking over their shoulder.”

Mendel stressed that if the culture of secrecy is to be turned, giving officials the confidence to apply the law is key.

“Everyone should be free of liability if they act in good faith,” he said, adding: “The risk of them actually exposing information that shouldn’t be disclosed is negligible. We have thousands and thousands of examples in every country in the world where (civil servants) don’t disclose information that should be disclosed and almost no examples of officials disclosing information which shouldn’t be disclosed, so the risks associated with this protection are nil and it’s very important.”

Such protection is just one of a number of actions which should be taken to ensure that civl servants not only do not feel “threatened” by the FOIA, but also buy into it.

As a start, they must be a part of a broad public consultation process that should accompany the introduction of an FOIA, said Mendel.

To date, that process has yet to take place in The Bahamas, with neither civil society, the media, or the civil service formally consulted, and neither has the government stated an intention for this to occur.

Mendel said: “If the civil service feel like this is something that is being pushed on them by an irate corporate or NGO sector that wants to control them and hold them accountable or whatever then that’ll be kind of bad optics from the beginning.

“What you often see is there’s an open process, the government will hold consultations and there’ll be a white paper and people give submissions, and people will write pieces in the newspaper, but civil servants will not be included in that, but they’ll have another discussion kind of behind your back with government and they’ll say,’Well, we can’t have this’ and ‘We need to protect ourselves’ – that’s a very unfortunate way for it to happen.”

“Public officials are citizens. They’re not this kind of strange breed of aliens that are governing us. It sounds a bit silly but it is an important point and saying to them, ‘Look, this will mean you have to share information you didn’t share previously, but that’s going to make The Bahamas a better country and a better society and that’s the society that you live in’.”

Mendel said having an FOIA in fact has specific direct benefits for the civil service beyond the general improvements to governance, accountability and service delivery that should accrue to society at large.

“Openness is basically a guarantee of protection for honest officials. My wife is a senior civil servant in Canada and as soon as she feels she is being pressured or levered into doing something that she is not uncomfortable with she writes a memo to file explaining that…that is basically saying, ‘Here’s my side of the story’. And she does that very explicitly.

“So in general openness protects honest officials from getting dumped on or screwed by the system. I don’t know whether that’s an issue in the Bahamas but it is in most systems at least to some extent. It prevents officials taking the rap, even if it’s a small rap, when the minister may have been the one who pushed for it to happen.”

‘MOTHERHOOD AND APPLE PIE’

The government’s delay in enacting the FOIA and the scepticism about their commitment to transparency that is building as a result comes at a point when, elsewhere in the world, arguments against enacting FOIAs are becoming increasingly scarce.

“In many places it’s very easy to build a strong coalition of support around this issue because it’s motherhood and apple pie,” he told .Digital.Disclosure.

“It’s just obvious that openness is a good thing and that the government, which is owned by the people should be responsible to the people and accountable to sharing information with them. These are just basic concepts,” he said.

This is so much the case that freedom of information is now guaranteed under the law in over 90 countries and has evolved to be regarded as a human right under international law.

Mendel is sceptical about whether it’s actually possible to have good governance and true democracy in The Bahamas – or anywhere – without an FOIA.

“Theoretically a government could be very open without one, just on a sort of policy basis, or a practice basis, but in reality that never happens. So in reality, no you can’t have robust good governance (without an FOI).

“Information is power and the culture of secrecy and the tendency of officials to kind of stand guard over the information they control prevents in practice the kind of openness that is required for good governance without a FOI law. A FOI law gives you the legal right to get it then they can only screw around so much, as it were. Or maybe a good way to put it is that the quality of governance will improve with an access-to-information law. Wherever you are at now, it will improve.”

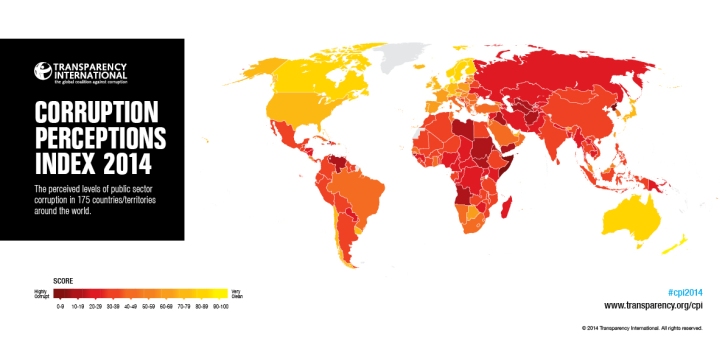

This conclusion is both intuitively sound and supported by examples from all over the world where FOIAs have been implemented, despite the fact that both corruption and good governance are difficult to measure.

“There is masses and masses of anecdotal evidence of where FOIAs are used to expose corruption to expose mismanagement or waste.”

“The high profile use of FOI laws is in the exposure of corruption and of course the media and civil society love that…It’s a very important benefit of these laws and it also goes some way towards answering the complaint about the costs of these laws, because you don’t have to reveal a lot of corruption or mismanagement before you start to recoup more than the costs of running the system.”

But having an FOIA is not just about the “news sexy” issues of corruption and mismanagement, it’s also about empowering the average man to have greater control over small community issues that could affect his own life in a very direct way – like new roads or commercial developments proposed in your neighbourhood.

“Using these laws people can engage more effectively they can get the information they need to participate in a policy process, a planning process, whatever it may be. It’s also important) in terms of accountability, not just corruption but just identifying waste, development projects that are off kilter, or not hitting their desired targets in the right way. So it just contributes in a general and positive way to foster public engagement in all of the processes the government undertakes, which creates ownership, creates buy-in, and not always but generally speaking improves those processes,” he said.

It’s beyond time that a Bahamian government recognised the right of its citizens to access information it collects on their behalf using public funds.

Whether or not the government does decide to wait until 2016 to enact the FOIA – and they need not – the RTI rating and Mendel’s analysis shows the path that the government should immediately begin to take in making amendments to the law.

Such improvements are necessary if the government wishes the law to be anything but a paper tiger, or for the media and the public at large to judge it to be even semi-serious about much-needed transparency and accountability.

Click on the link below to view the full Centre for Law and Democacy Right to Information (RTI) Rating of The Bahamas FOIA 2012.

Bahamas.FOI.Jan15.score

Click here to view the FOIA 2012

Bahamas FOIA 2012

What do you think? Leave comments via the link to the left of this post.